The Power of People in Pandemic Times - Driving Supply Chain Resilience through Corporate Culture

The assertion “Our people are what sets us apart from our competitors” is a common statement made by nearly every company, highlighting the significance of their people as the most valuable asset. Similarly, a corporate culture emphasizing risk awareness and learning from experiences has played a key role in shaping supply chain resilience (SCRES) amidst competitive dynamics in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Employee engagement, communication, and collaboration, as dimensions of SC risk awareness, determine the effectiveness of firms’ cultures in handling large-scale disruptions with robustness and agility. Additionally, the COVID-19 crisis has had a positive impact on firms’ learning orientation. The crucial necessity of digital supply chain (SC) transformation to enhance SCRES under pandemic conditions has further reinforced the need for dynamic adaptation and reconfiguration of firms’ culture and employee skillsets through digital upskilling.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of resilient SCs, emphasizing the ongoing need for their smooth operation [1]. Companies have primarily focused on accelerating the implementation of SC improvement initiatives. A firm’s crucial challenge is to ensure continuous SC operations in the face of growing complexity, vulnerability and volatility of global intertwined SC networks [2]. Although economies and societies have been exposed to multiple extreme SC disruptions caused by crises – such as epidemics (Ebola, SARS), natural disasters (floods, earthquakes, hurricanes) or financial crises [3] – several studies have shown that, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, many firms were not prepared and showed a fundamental lack of SC robustness and agility to cope with the disruption [4].

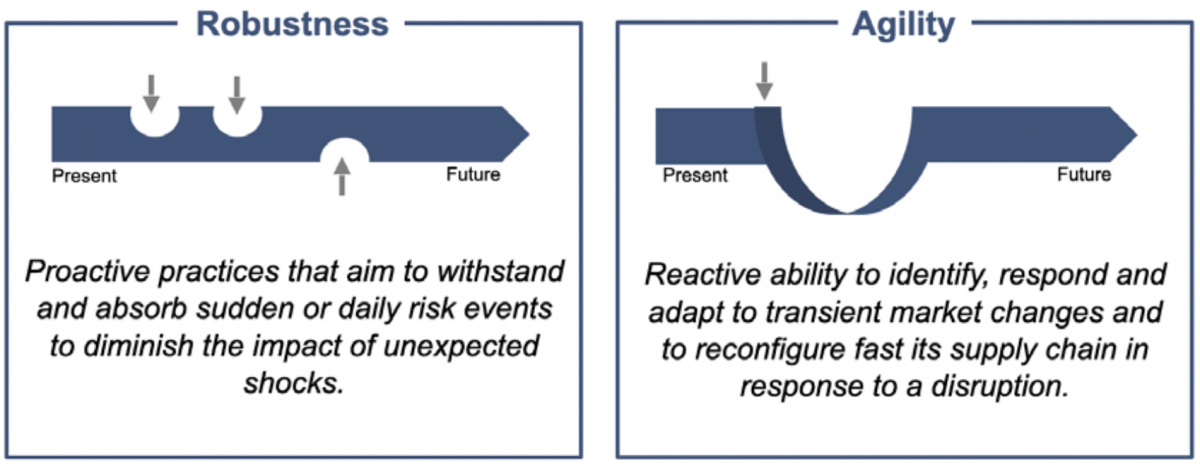

Figure 1 illustrates that two core strategies for coping with exceptional SC disruptions exist, such as the COVID-19 pandemic [5]. Proactive strategies target the ex-ante disruption phase and describe measures taken before SC disruption occurs; they require the ability to anticipate sudden risks and thus absorb or reduce the impacts of disruption. Reactive strategies target the ex-post-disruption phase; they require that firms’ are able to reconfigure their capabilities to respond and adapt to dynamic market changes, firms with agile SC strategies can rapidly identify and react to unexpected changes. Considering how important it is that firms have proactive and reactive SC capabilities, we define SCRES as the ability of firms to prepare for unexpected risk events, respond to potential disruption and to recover quickly, either by restoring their original operating state or by progressing to a new, more desirable operating state [3, 5]. In this context, studies have acknowledged that corporate culture can be a key component in firms’ response strategy to unanticipated and sudden external threats [6, 7] as the past couple of years have witnessed an unprecedented surge in the demand for skilled SC professionals. Consequently, a favorable and positive corporate culture that values continuous learning and development creates an environment conducive to SC risks and employee upskilling. [8].

The objective of this study is to provide a comprehensive outline of the significance of corporate culture in enhancing supply chain resilience, particularly with regard to fostering SC risk-awareness and advancing digital upskilling. The study endeavors to offer clear guidance for firms to take actionable measures in this regard.

Figure 1: Creating resilient supply chains requires mitigation through

proactive and reactive strategies [1, 2, 3, 5].

Corporate culture: key supply chain value driver during crisis times

According to Schein (1996, 231), culture is defined as often ‘taken-for-granted, shared, tacit ways of perceiving, thinking, and reacting, [but is] one of the most powerful and stable forces operating in organizations’ [9]. Culture refers to the pattern of shared values and beliefs in an organisation that helps employees understand organisational functioning and, thus, provide them with norms for behaviour in the firm Moreover, the concept of corporate culture positively influences employee identification, their attitude, willingness to share informatiom and sense of belonging within organizations [10]. As a consequence, corporate culture is a key factor influencing how organizations and SCM react and respond strategically to sudden large-scale disruptions. A strong cultural fit across buyers and suppliers could be highly beneficial in terms of managing joint inventory, cooperative relationships and maintaining SC performance, while a weak cultural fit could hamper SC collaboration and overall performance [6, 7, 8].

The centricity of humans and their influence on the performance of multiple SC stages make employees valuable and a competitive differentiator [8, 11]. It is essential to acknowledge the interpersonal aspects of all inter-organisational SC partners. Thus, corporate culture is the organisational ‘DNA’ that represents a set of principles with which employees can respond rapidly to unexpected SC risk events [12]. And it is in time of crisis, exemplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, that strong organisational cultures can foster a collective spirit of perseverance [13]. A risk-aware culture might contribute to firms’ successful business performance in times of crisis and SC disruption [14]. In the same vein, empirical evidence shows that SC employee skillsets and experiences affect a company’s SCM and SCRES [3, 15]. Applying digital technology, such as big data analytics, cloud computing and artificial intelligence, can strengthen collaboration and increase the visibility of information. Accordingly, adopting digital technologies might play a powerful role in SCRES, even for firms that lack skills, knowledge and experience [16, 17]. Hence, learning from past experience (e.g. training programmes) can bolster SC professionals’ (digital) upskilling and knowledge, allowing firms to adapt and reconfigure their SCRES practices to better respond to sudden SC disruption in the future.

Research design

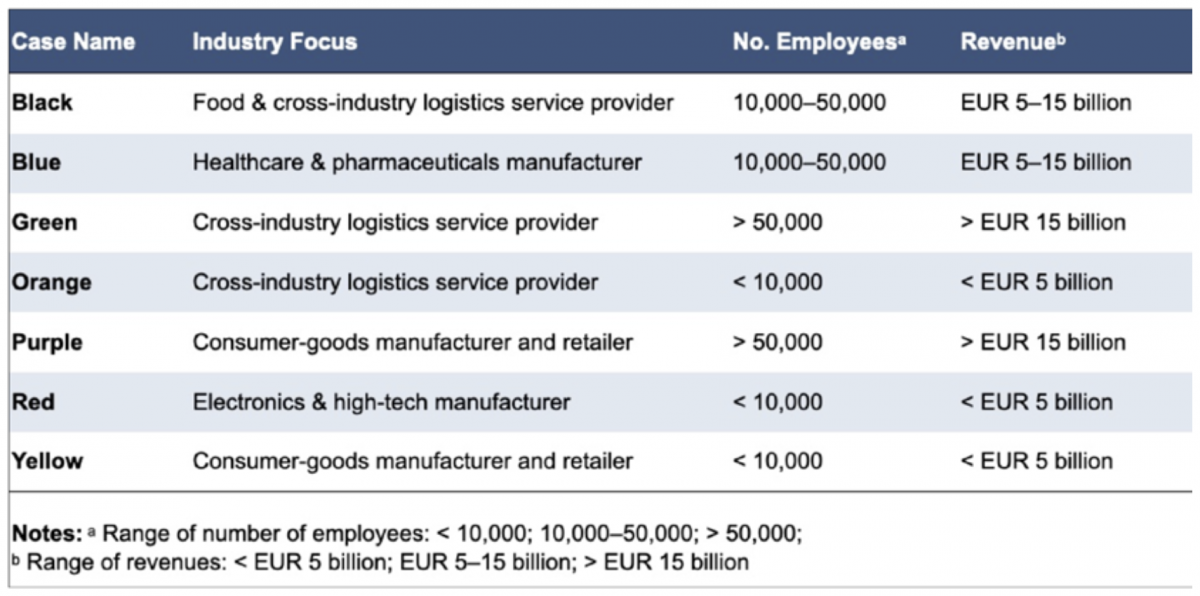

The COVID-19 crisis has created many opportunities for meaningful and practical research on SCRES from a holistic process perspective. Hooks et al. (2017, p. 2) state that “resilience can only be truly tested in times of adversity or crisis.” [18] The present study follows a multiple case-study design which is well suited for the investigation of complex phenomena such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and particularly for research that focus on processes [19], such as SCM. Our multiple case-study approach follows the recommendation of Eisenhardt (2021) emphasizing that four to ten cases appear to be adequate for a multiple case-study design [19]. To allow for generalisability, we decided not to limit our sample to a single industry or a single product type [20]. The case sample comprises companies headquartered in Europe to ensure that all share similar infrastructural, legal and political environments. All of the selected firms – from manufacturers and retailers of consumer goods to healthcare, electronics and logistics service providers – operate in global SCs and were strongly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (see Table 1). However, to represent a range of perspectives, we deliberately selected firms of various sizes and with a range of industry focuses and practices to deal with sudden shocks.

Data collection took place in the year 2022 via Zoom or Skype. All interviews were semi-structured and based on a predefined interview questionnaire. An extensive literature review guided the development of the interview questionnaire [20]. We conducted a total of 15 interviews with executives, experts, and managers from company headquarters to understand professional involvement in SCM during the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The interviews lasted between 50 and 70 minutes and were recorded and transcribed. To avoid any potential errors and misunderstandings, each interviewee received a copy of the transcript. To facilitate data triangulation and safeguard construct validity, we added the interviewers’ real-time notes to all transcripts [19, 20, 21].

Our data analysis started with an open coding process to provide initial structure by evaluating the large amount of unstructured information in the data collected from each interview [22]. We applied an iterative process of continuous reflection to connect information, define analytical clusters and build key thematic categories [22]. Thus, all interview transcripts were thoroughly examined to determine relevant information, paraphrase important statements and categorize them thematically. Next, we incorporated secondary data (e.g., from company websites, newsletters and industry reports) into our case-study database to corroborate specific interview statements and, therefore, to increase reliability while reducing potential case data bias. Then, we focused on within-case analyses to develop meaningful individual case profiles and acquaint ourselves with each case. In the next step, we conducted a cross-case analysis to look for connections, recognize patterns and identify the most meaningful insights into the practices the seven case company had employed to strengthen their SCRES during the pandemic [19, 20].

Figure 2: Case company overview.

Engage, communicate, collaborate: SC risk-awareness during pandemic times

Employee engagement. Interviewees mentioned employee engagement as a critical element in successfully adapting to low-probability, high-impact disruptions. Interviewees from all seven case companies reported that their organizations did their best at the beginning of the pandemic to create a working environment in which employees felt safe. For this purpose and to stimulate a positive team spirit while working from different locations, the case companies held regular update meetings and shared daily or weekly newsletters to inform employees of the latest COVID-19 developments and initiatives.

However, we found evidence that not all companies had a risk-aware culture before the pandemic disruption. For instance, interviewees representing cases Black, Green and Orange mentioned that, because of their nature as global LSPs, their organizations were already accustomed to dealing with a wide range of operational SC risks and ensuring resilience in their SC networks: they had business continuity and predefined communication plans in place to buffer disruptions in their transportation, warehousing and distribution networks. Nevertheless, company representatives from the logistics service industry reported serious shortcomings in their initial responses to pandemic-related disruptions, highlighting a weak strategic focus and commitment to exceptional disruptions during the initial COVID-19 outbreak. For example, the clarification of roles and responsibilities across different teams and departments or the communication cascades and structures impeded the effectiveness of initial responses to pandemic disruptions. Consequently, employees suffered a lack of trust and decision-making autonomy. Suddenly, professionals felt they were working in a hierarchical environment with leaders and managers who needed to authorize nearly all decisions and countermeasures, contradicting the prior experience and mindset of empowerment when operational SC disruptions had occurred.

This slower decision-making, lower employee motivation and overwhelming need for leadership coordination later required a fundamental shift towards more employee engagement as the pandemic took hold. At Black, for example, employees created a community and knowledge platform to encourage employees not only to share effective countermeasures and best practices to handle the disruption, but also to share new ideas for customer and supplier interaction. Such initiatives facilitate better initial disruption response, improve information exchange, accelerate decision-making and empower employees when handling exceptional threats. Interviewees representing Yellow reported that creating an open and creative working environment (e.g. from home or cross-team workstations in the office) were an important factor in stimulating trust and empowerment. Interviewees from Blue and Red said that dedicated communication plans and cross-functional employee risk management training had been in place for some time, while interviewees representing Blue explicitly acknowledged that employees’ experience of other extreme disruptions (e.g. Hurricane Katrina) was invaluable in the initial pandemic response.

Communication. The informants in our study reported effective communication through human interaction as a key lever for an appropriate risk-aware culture during the pandemic. All interviewees reported that switching to new online communication tools at the outbreak of the pandemic was a challenging, sometimes overwhelming task. Thus, intra- and inter-organisational communication based on human interaction was a decisive factor to maintain global SC operational performance and mitigate the pandemic-related SC disruptions. Our informants pointed out that employees’ communicative and relationship-oriented skillset was of utmost importance to share data and updates on pandemic-related SC disruption and enable fast reactions. Such communication permitted open information-sharing in informal ways that were frequently much faster than official company statements, top-down communication from senior management or official media, all of which take time and risk sharing information that is out of date. For instance, Blue and Yellow organized regular daily exchanges between key customers and suppliers to ensure that all parties had access to the latest and most meaningful information all times. Additionally, Black, Green and Purple used SC visibility platforms to obtain relevant and accurate inter-organisational information and foster smooth information exchange via internal communication platforms. Red highlighted the importance of maintaining close personal contacts as the company had to negotiate a shortage of packaging material caused by cross-border shutdowns. For instance, to find a solution rapidly, one Red employee called a long-standing personal contact at a seldom-used back-up supplier. The two parties were able to arrange the required packaging material between them during this exceptional situation, and Red subsequently became the only company that could sell the product on the market.

Collaboration. Data from our interviews revealed a clear need for improvement in cooperation amongst SC network partners to handle the disruption the COVID-19 pandemic caused. Several informants reported that a narrower focus on improving relationships amongst multiple SC members helped them maintain the flow of goods and materials. Moreover, knowledge-sharing amongst key SC partners was essential in keeping all parties informed of the current status of the disruption. Although some firms were reluctant to share information, most firms found that collaborations intensified and became more open during the pandemic, which helped all partners react more effectively. Interviewees representing five out of the seven companies in our study reported that they encouraged employees not only to share data and information but also to initiate joint problem-solving approaches across departments, locations and preferred SC members as a specific measure to respond to the disruption.

For example, Purple exemplified close collaboration with its customers: after a two-month development phase, the firm launched an intuitive and easy-to-use portal with three key customers. The idea was to simplify the SC process and foster superior customer service through trust and openness. As the interviewee representing Purple stated: ‘The best customer service is when we do not have to answer any phone calls.’ Core data – such as product availability, order capacity, pricing and delivery times – were updated and made available in the portal to allow 24/7 customer service while managing employee shortages. This illustrates that cross-organisational collaboration can prevent the breakdown of operational SC networks, closely connect key SC partners and bolster SCRES in uncertain and rapidly changing environmental conditions.

Figure 3: The power of corporate culture in driving supply chain resilience.

Go digital or go home: key learnings from the pandemic disruption

Revamping a culture that embraces change and digitalisation. Analysis of our interview data revealed that a corporate culture needs to inject a DNA of willingness to change, adapt and reconfigure in response to extreme turbulence in dynamic environments. Our case informants emphasized the clear need to learn how to cope with exceptional disruptions in the future, and therefore to consider the change caused by the pandemic as an opportunity to further shape organisational culture.

Culture has been defined as a set of shared values and beliefs. All company representatives in our study – but those from Black, Green and Orange in particular – emphasized that the communication of organisational values, attitudes and purpose needed to be improved and shared amongst both employees and key partners. A Blue interviewee suggested that, because large-scale disruptions are largely out of firms’ control, compiling knowledge from previous crises into a ‘playbook’ or guide that suggests ways to handle low-probability, high-impact SC disruptions would be highly beneficial. However, a strong prerequisite is that the organisational culture tolerates a degree of failure. In this vein, interviewees stated that, for instance, Blue will work to reinforce trust in and empowerment of operational staff to take their own decisions when needed; Black will arrange cross-functional and cross-locational workshops to establish a Strategic Culture Wheel comprising guiding principles (e.g. customer-centricity, communication, team spirit, trust, empowerment, leadership values) to engender a mindset across the organization that embraces digital. However, interviewees were careful to emphasize that such initiatives should be driven bottom-up to allow rapid decision-making and foster simple digital tool developments. A representative of Purple stated that, because of the COVID-19 pandemic’s effect on the global cascading of knowledge, they conceived a mandatory online training programme to provide professionals with the fundamental risk management skills, necessary behaviours and most relevant ‘dos and don’ts’. Similarly, Green, Orange and Yellow organized cross-functional training and workshops to establish a more digital culture with specific social competencies, such as pyramidal communication, problem-solving or working in a virtual team environment. Overall, five out of the seven case company representatives reported the use of strategic collaborative approaches with key customers, suppliers and partners to strengthen SC cooperation, stimulate personal relationships and enhance an open information-exchange culture.

Digital upskilling through effective training programmes. The key importance of the human factor in SCM and SCRES is reflected in our own data, as representatives of all our case companies said that employee skillsets, knowledge and experience were decisive in responding and adapting to the outbreak of COVID-19 and as the pandemic took hold. However, all interviewees agreed that the digital transformation of organisational and SC processes from office to mobile and/or flexible shift working was a fundamental challenge. Yet, it was vital to adopt new innovative collaboration tools or digital platforms, or to digitize and simplify processes to effectively manage global SC networks during the pandemic. Unsurprisingly, all company representatives emphasized that a supportive corporate culture that embraces digital SC technologies was key to coping with such exceptional SC disruption.

Nevertheless, since all informants were impacted by the pandemic, our case data revealed a significant digital skills gap in the application of technology across the studied firms. Although the pandemic forced firms to deprioritize strategic projects, including digitalisation initiatives, all our case informants reported that strengthening digitalisation via ‘digital upskilling’ of their employees was a key component in adapting to such major disruption in a hypercompetitive and dynamic business environment. Overall, our informants emphasized the importance of adjusting culture with an innovation-oriented leadership mindset and providing training to foster a more diverse and organisational digital skillset to exploit the full potential of a technology-driven SC network. Moreover, our informants suggested that this may require that fewer SC managers are involved in standardized and repetitive tasks or processes, and that more SC employees assume more data- and technology-driven roles.

The findings of our study suggest that changing the scope of SC job roles creates new opportunities to strengthen SCRES. For instance, a representative of Purple stated that for managers to handle customers more efficiently through the new collaboration portal, they would need some expertise in data science and coding. Moreover, Purple’s IT & Digitalisation department would need to train SC employees in data science and robotic process automation to accelerate SC automation, facilitate rapid information exchange, improve customer service and enhance SC efficiency. A representative of Blue expected that the firm would comprehensively review its current SC job roles and establish digital solutions as a core ingredient of its SCRES. For that reason, the company hired an external consulting firm to evaluate its SC professionals’ current competency profiles and derive their personalized ‘digital learning journey’. A representative of Black considered that big data analytics and artificial intelligence (e.g. machine learning) would quickly become key technologies in future SCs, and that training will therefore be provided to acquire the essential skills and competencies needed to work in a data-driven SC setup. Hiring external experts was also mentioned as an option however the additional salary burden might widen any pay gap within the company or simply be unaffordable. Alternatively, Orange, Red and Yellow saw partnering with external institutions as the most effective way to strengthen digital skillsets and initiate ‘agile projects’. Finally, a representative of Green stated openly that the company has grown with rather conservative values: leadership and managers lack both digital skills and digital mindsets. Thus, both hierarchies will participate in a digital leadership programme to develop management’s purpose in and knowledge and experience of digitalisation.

Conclusion and managerial implications

The global business economy has had to find ways to handle the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic – which will continue to disrupt SC networks for some time – and no doubt there will be similar exceptional disruptions in the future. The study has investigated empirically how these firms’ risk-aware and learning-oriented corporate cultures affected their SCRES during the COVID-19 crisis. It has become evident that a supportive and adaptive corporate culture plays a critical role in enabling firms to respond effectively to unprecedented SC disruptions. Specifically, our research examines how various aspects of corporate culture, including employee engagement, communication, collaboration, change management, and digital upskilling, contribute to strengthening SCRES. Hence, our results are based on empirical evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic and provide several managerial implications.

First, managers need to ensure that their firms can respond to and recover from exceptional SC disruption at least as robustly and agilely as their competitors. Risk-aware leaders and managers should foster a corporate culture of trust and empowerment with forward-looking perspectives to engage SC employees. Exchanging expertise, sharing experience and best-practice approaches from the COVID-19 pandemic must be turned into proactive action, for example by establishing cross-functional employee risk management training programmes and creative working environments that stimulate unconventional thinking to find new ways of handling disruption.

Second, we encourage managers to create a culture that is unafraid of risk and that embraces open communication (internal, external and amongst all SC stakeholders) to increase information exchange across globalized SC networks. Our findings show that this will improve companies’ ability to anticipate – and thus to react more quickly than their competitors to – unexpected SC disruption.

Third, our results highlight that superior inter-organisational SC collaboration consolidates relationships with SC partners. Engaging in joint initiatives, building trust and being willing to share information more openly will enable managers to improve their portfolio of measures to maintain SCRES and thus develop better preparation and response strategies.

Lastly, we strongly recommend that managers deploy training and education programmes to reinforce digital upskilling and give SC professionals the skillsets required to exploit the full potential of emerging technologies. Our study confirms that digital SC skills, knowledge and experience are invaluable in managing SC uncertainty today.

Schlüsselwörter:

COVID-19 pandemic, supply chain resilience, supply chain disruption, culture, learning, digital upskilling, digitalisation, transformationLiteratur:

[1] Hohenstein, N.-O.: Supply chain risk management in the COVID-19 pandemic: strategies and empirical lessons for improving global logistics service providers’ performance. In: The International Journal of Logistics Management, 33 (2022) 4, pp. 1336-1365.

[2] Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A.: Viability of intertwined supply networks: extending the supply chain resilience angles towards survivability. A position paper motivated by COVID-19 outbreak. In: International Journal of Production Research, 58 (2020) 10, pp. 2904-2915.

[3] Hohenstein, N.-O.; Feisel, E.; Hartmann, E.; Giunipero, L.: Research on the phenomenon of supply chain resilience. In: International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 45 (2015) 1/2, pp. 90-117.

[4] Van Hoek, R.: Research opportunities for a more resilient post-COVID-19 supply chain – closing the gap between research findings and industry practice. In: International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 40 (2020) 4, pp. 341-355.

[5] Sturm, S.; Hohenstein, N.-O.; Birkel, H.; Kaiser, G.; Hartmann, E.: Empirical research on the relationships between demand- and supply-side risk management practices and their impact on business performance. In: Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 27 (2022) 6, pp. 742-761.

[6] Das, K.; Lashkari, R. S.: Risk readiness and resiliency planning for a supply chain. In: International Journal of Production Research, 53 (2015) 22, pp. 6752-6771.

[7] Chunsheng, L.; Wong, C. W.; Yang, C.-C.; Shang, K.-C.; Lirn, T.: Value of supply chain resilience: roles of culture, flexibility, and integration. In: International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 50 (2020) 1, pp. 80-100.

[8] Hoberg, K.; Thornton, L.; Wieland, A.: How to deal with the human factor in supply chain management?. In: International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 50 (2020) 2, pp. 151–158.

[9] Schein, E. H.: Culture: the missing concept in organization studies. In: Administrative Science Quarterly, 41 (1996) 2, pp. 229-240.

[10] Liu, H.; Ke, W.; Wei, K. K.; Gu, J. and Chen, J.: The Role of Institutional Pressures and Organizational Culture in the Firm’s Intention to Adopt Internet-Enabled Supply Chain Management Systems. In: Journal of Operations Management, 28 (2010) 5, S. 372-384.

[11] Hohenstein, N.-O.; Feisel, E.; Hartmann, E.: Human resource management issues in supply chain management research: a systematic literature review from 1998 to 2014. In: International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 44 (2014) 6, pp. 434-463.

[12] Sheffi, Y.: Preparing for the big one. In: IEE Manufacturing Engineer, 84 (2005) (5), pp. 12-15.

[13] Lund Pedersen, C.; Ritter, T.: Preparing Your Business for a Post Pandemic World. In: Harvard Business Review (2020). URL: hbr. org/2020/04/preparing-your-business-for-a-post-pandemic-world, time of access: 10 May 2023.

[14] Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Childe, S. J.; Roubaud, D.; Fosso Wamba, S.; Giannakis, M.; Foropon, C.: Big data analytics and organizational culture as complements to swift trust and collaborative performance in the humanitarian supply chain. In: International Journal of Production Economics, 210 (2019), pp. 120-136.

[15] Mello, J. E.; Stank, T. P.: Linking firm culture and orientation to supply chain success. In: International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 35 (2005) 8, pp. 542–554

[16] Büyüközkan, G.; Göçer, F.: Digital Supply Chain: Literature review and a proposed framework for future research. In: Computers in Industry, 97 (2018), pp. 157–177.

[17] Ralston, P.; Blackhurst, J.: Industry 4.0 and resilience in the supply chain: a driver of capability enhancement or capability loss?. In: International Journal of Production Research, 58 (2020) 16, pp. 5006- 5019.

[18] Hooks, T.; Macken-Walsh, A.; McCarthy, O.; Power, C.: The impact of a values-based supply chain [VBSC] on farm-level viability, sustainability and resilience: Case study evidence. In: Sustainability, 9 (2017) 2, pp. 267.

[19] Eisenhardt, K. M.: What is the Eisenhardt method, really? In: Strategic Organization 19 (2021) 1, pp. 147–160. [20] Yin, R. K.: Case Study Research and Application: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA 2018.

[21] Gibbert, M.; Ruigrok, W. and Wicki, B.: What passes as a rigorous case study? In: Strategic Management Journal 29 (2008) 13, S. 1465-1474.

[22] Corbin, J. M.; Strauss, A.: Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. In: Qualitative Sociology, 13 (1990) 1, S. 3-21.